A Document That Changed America—and Changed Me

I’ve stood on the summit of Half Dome. I’ve backpacked through Yosemite’s wilderness dozens of times. I’ve watched sunrise spill into Yosemite Valley more times than I can count.

And yet, one of the most meaningful Yosemite experiences of my life didn’t happen inside the park at all.

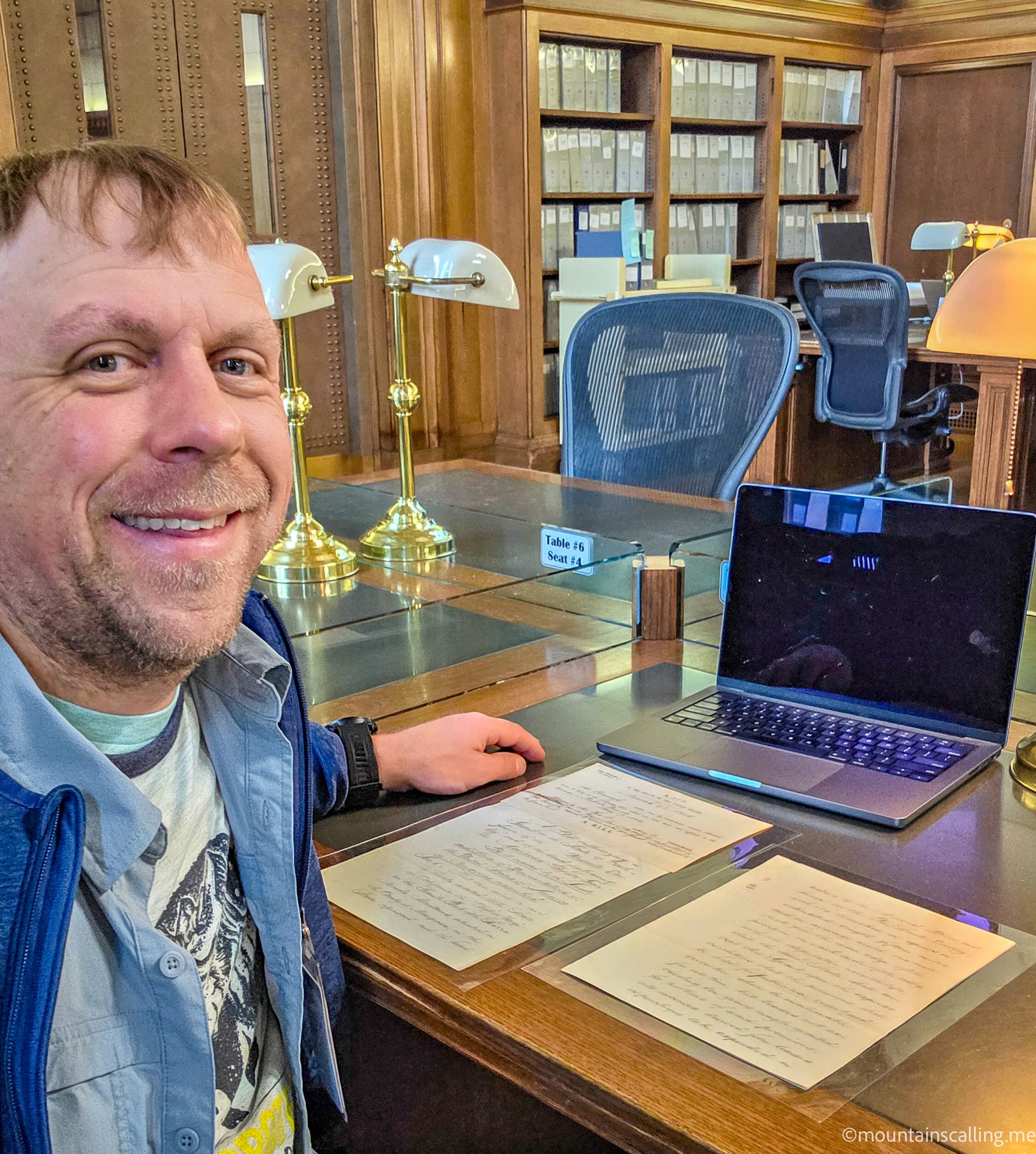

It happened in a quiet research room, holding historic paper that helped change America—and, in a much quieter but deeply personal way, changed me too.

The Yosemite Grant

The Yosemite Grant is not just a historical curiosity. It is a foundational document—arguably the first time the United States formally set aside land not to exploit, but to protect, preserve, and share with the public.

Long before there was a National Park Service, before “public lands” were a national value, this document made a radical claim: some places are too important to lose.

It was a document that reshaped how a nation thought about land—and what it owed to the future.

What the Yosemite Grant Was — and When It Was Created

The Yosemite Grant was enacted on June 30, 1864, when the United States Congress passed legislation granting Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias to the State of California.

The land was to be held inalienable for all time for public use, resort, and recreation.

This was a radical departure from prevailing federal land policy. At the time, most public land was viewed primarily as a resource to be settled, logged, mined, or sold. The Yosemite Grant represented a dramatic shift in thinking: land could be protected not because it was unproductive, but because it was irreplaceable.

For the first time, the federal government formally chose preservation over extraction—a choice that would ripple outward, shaping America’s relationship with its landscapes for generations.

America in 1864: A Nation at War

The timing of the Yosemite Grant makes it even more remarkable.

In 1864, the United States was deep in the American Civil War. The nation was divided, resources were strained, and the outcome of the war—and the future of the country itself—was still uncertain.

This was not a moment of peace or excess optimism. It was a moment defined by sacrifice, loss, and national survival.

And yet, even in the midst of war, the United States chose to think beyond the present moment. It chose to protect a place of extraordinary natural beauty for generations that would come long after the conflict had ended—a quiet, hopeful act that helped shape what America would become.

Who Signed the Yosemite Grant Into Law

The Yosemite Grant was signed into law by Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln is most often remembered for preserving the Union and ending slavery, but his role in conservation history is less widely known. By signing the Yosemite Grant, Lincoln helped establish a principle that would shape American land stewardship forever.

That a president consumed by war, emancipation, and national survival would also take the time to protect a distant landscape in California speaks to the depth of the idea behind the Grant.

This was not a political afterthought. It was a statement about what kind of nation America aspired to be.

Before National Parks Existed

It is important to understand what the Yosemite Grant was not.

It did not create a national park. The National Park Service would not exist for another 52 years, and Yellowstone National Park, the first official national park, would not be established until 1872.

Instead, the Yosemite Grant functioned as a prototype.

It tested the idea that land could be protected by the federal government and held in trust for the public. The success of this experiment helped pave the way for Yellowstone, the National Park Service, and ultimately the entire U.S. public lands system.

A single document quietly set in motion a national legacy.

Why the Yosemite Grant Is Nationally Historic

The Yosemite Grant didn’t just shape Yosemite.

It helped define an entirely new American idea: that certain landscapes belong to everyone—not the wealthy, not private interests, not industry, but the public, forever.

Every national park that came after traces its lineage back to this moment. The entire concept of public lands in the United States rests, in part, on this single decision.

This is how a document changes a country.

Why This Matters to Me Personally

Yosemite isn’t just a place I visit. It’s a place that shaped who I am.

For years, Yosemite has been a constant in my life—through different seasons, different chapters, different versions of myself. I’ve known the park through exhaustion, awe, solitude, sadness and joy.

Holding the Yosemite Grant felt like tracing all of that back to its beginning—not just Yosemite’s story, but my own connection to it.

The Power of Holding the Original Document

There is something profoundly grounding about holding an original document like this.

The paper is real. The ink is real. The signatures are real. This wasn’t an abstract idea—it was a deliberate choice, made by real people, at a moment when Yosemite’s future was far from guaranteed.

In that moment, I felt a strange collapse of time. The distance between 1864 and today disappeared. Yosemite suddenly felt not ancient—but newly protected, again.

The document that helped change America quietly changed how I understood my own relationship to the park.

The National Archives Experience

Experiencing the National Archives as a researcher was its own revelation.

This is where the nation’s memory lives—not as scanned PDFs, but as carefully preserved, deeply respected artifacts. The staff, the process, the care taken with each document—it all reinforces how seriously this history is protected.

Just as Yosemite preserves landscapes, the National Archives preserves the documents that shaped the nation—and the ideas that still guide it.

A Different Kind of National Park Experience

I’ve had countless unforgettable experiences inside national parks.

But this was something different. This was a reminder that the parks don’t begin at trailheads—they begin with ideas, decisions, and documents that quietly set the future in motion.

Holding the Yosemite Grant may be the most meaningful National Parks experience of my life precisely because it revealed why Yosemite exists at all.

Responsibility and Continuity

The Yosemite Grant is more than history. It is a responsibility passed forward.

Every time we step onto protected land, we are beneficiaries of a choice made long before us. Experiencing the Grant firsthand—reading it, studying it, and spending time with it—made that responsibility feel tangible and personal.

What stayed with me was not a single moment, but the entire arc of the visit. From entering the National Archives as a researcher, to engaging deeply with the document that helped give rise to Yosemite, to eventually returning to the public spaces of the building, the experience unfolded as a kind of quiet reckoning with American history.

After finishing my work with the Yosemite Grant, I walked through the front doors of the National Archives and viewed the three founding documents of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

Seeing them after spending time with the Yosemite Grant was deeply moving.

Together, those four documents—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the Yosemite Grant—represent moments when people chose to think beyond themselves. They reflect belief in shared responsibility, in restraint, and in the idea that the future mattered enough to protect.

Being there with those documents stirred genuine pride in the people who wrote them. Pride in the care they took. Pride in the foresight they showed. Pride in the values they were willing to commit to words—and, in the case of Yosemite, to land.

At the same time, the experience carried a quieter weight. A recognition that these ideals are not fixed or guaranteed. They endure only through attention, care, and recommitment over time.

That realization didn’t feel abstract. It felt personal—and grounding. A reminder of what has been entrusted to us, and of the responsibility that comes with inheriting it.

Why Yosemite Matters to Me

That sense of responsibility did not feel heavy as I left the National Archives. It felt clarifying.

Because for me, that responsibility has always had a place to land. It lives in Yosemite—in the trails I return to, the quiet moments in The Valley, the way time seems to slow when you are paying attention. Yosemite is not an idea to me. It is lived, felt, and renewed each time I’m there.

The Yosemite Grant made it possible for that relationship to exist at all. Not just for me, but for millions of people who have found meaning, perspective, and belonging in that place. That is the lasting power of the document: it didn’t just protect land—it made experiences like mine possible, again and again, across generations.

Walking away from the Archives that day, I carried more than historical knowledge. I carried gratitude. Gratitude for the foresight that preserved Yosemite. Gratitude for the institutions that protect this history. And gratitude for the chance to connect those ideas to a place that continues to shape who I am.

National Parks remind us what we are capable of when we choose care over convenience, and stewardship over short-term thinking. Yosemite, in particular, has always offered that reminder to me—quietly, consistently, and without asking anything in return.

A document that helped shape America made Yosemite possible. And through Yosemite—through years of returning, learning, and listening—it shaped me too.

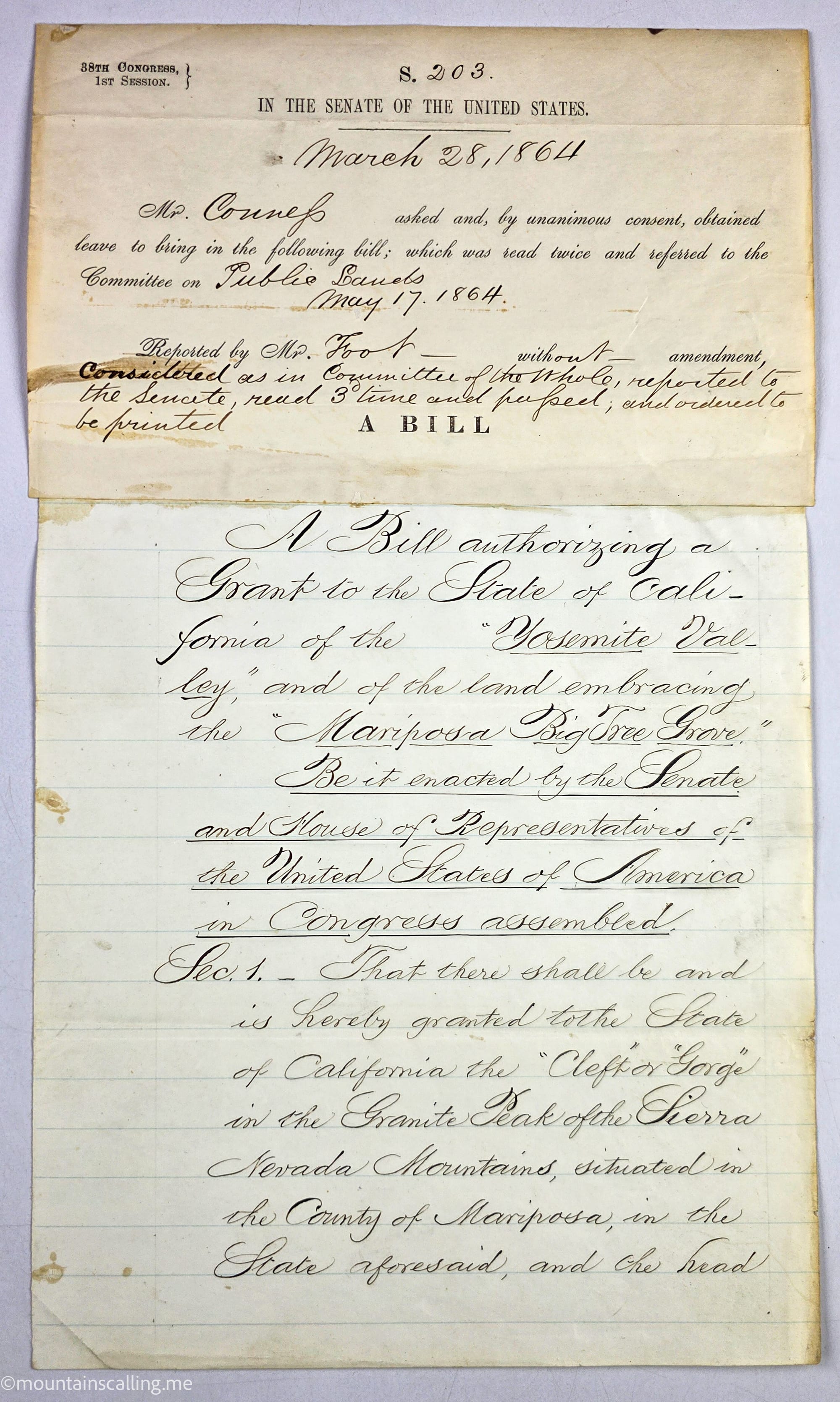

What follows is the exact text of the Yosemite Grant Act of 1864 as introduced and passed by Congress, reproduced verbatim so it can be read clearly without interpretation.

Yosemite Grant Act of 1864

38th Congress — 1st Session

Senate Bill No. 203

United States Senate

March 28, 1864

Mr. Conness asked, and by unanimous consent obtained, leave to bring in the following bill; which was read twice and referred to the Committee on Public Lands.

May 17, 1864

Reported by Mr. Foor without amendment, considered as in Committee of the Whole, reported to the Senate, read a third time and passed, and ordered to be printed.

A BILL

Authorizing a grant to the State of California of the “Yosemite Valley,” and of the land embracing the Mariposa Big Tree Grove

Section 1

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

That there shall be, and is hereby, granted to the State of California the “cleft” or “gorge” in the granite peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, situated in the county of Mariposa, in the State aforesaid, and the headwaters of the Merced River, and known as the Yosemite Valley, with its branches or spurs, in estimated length fifteen miles, and in average width one mile back from the main edge of the precipice, on each side of the valley; with the stipulation, nevertheless, that the State shall accept this grant upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation; shall be inalienable for all time; but leases not exceeding ten years may be granted for portions of said premises.

All incomes derived from leases of privileges are to be expended in the preservation and improvement of the property, or the roads leading thereto; the boundaries to be established at the cost of said State by the United States Surveyor General of California, whose official plat, when affirmed by the Commissioner of the General Land Office, shall constitute the evidence of the locus, extent, and limits of the said cleft or gorge; and the premises to be managed by the Governor of the State with eight other commissioners, to be appointed by the executive of California, and who shall receive no compensation for their services.

Section 2

And be it further enacted, That there shall likewise be, and there is hereby, granted to the said State of California the tracts embracing what is known as the “Mariposa Big Tree Grove,” not to exceed the area of four sections, and to be taken in legal subdivisions of one quarter section each, with the like stipulation as expressed in the first section of this act as to the State’s acceptance, with like conditions as in the first section of this act as to inalienability—yet with the same lease privilege—the income to be expended in preservation, improvement, and protection of the property; the premises to be managed by commissioners as stipulated in the first section, and to be taken in legal subdivisions as aforesaid; and the official plat of the United States Surveyor General, when affirmed by the Commissioner of the General Land Office, to be the evidence of the locus of the said Mariposa Big Tree Grove.